This is my (un)scientific, (non-)comprehensive, and (not at all) objective overview of the rise of collaborative storytelling: how we (more or less) got here, and where we may (kinda sorta) be heading. No particular axe to grind or agenda to sell, just my observations after watching this space for a few years.

Buckle up, this is the longest post I’ve ever written…

The history of collaborative storytelling goes back millennia…

Many of the oldest texts were collaborative stories that shared characters, settings, and backgrounds – collections of individual stories set in a shared “world” of common histories, mythologies, and understandings. The Greek mythology character, Jason (best known for leading the Argonauts on a series of adventures), is mentioned in several different texts by different authors across centuries of time.

The character of Merlin had a similar evolution. The persona we know today as Merlin was crafted over centuries by many individuals who collectively shaped the wizard by layering their own take on the previous version before passing it along for future writers.

Today, collaborative storytelling exists in many forms and utilizes many kinds of creative mechanics. With the advent of the Internet and the increasing tendency for consumers to produce their own content, the ability to collaborate on a project has never been easier. In fact, the line between producer and consumer is increasingly blurry, with formerly distinct roles like “performer” and “audience” overlapping in new models of entertainment. The last few decades have given rise to an explosion in forms of collaborative storytelling due to many factors.

…but let’s start with a definition.

How we got here is a story in its own right, but it makes sense to start with what I mean by the term, “collaborative storytelling.” With definition firmly in hand, we can turn to some of the more recent factors contributing to the practice, highlight certain examples, and touch on what the future of collaborative storytelling may hold.

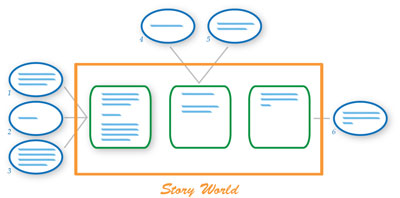

My preference is to view collaborative storytelling as branching down two narrative approaches: collaboration at the story level and collaboration at the storyworld level. The first path is, by definition, a group activity resulting in a single story, and the process for crafting that story can take many forms.

One example is the serial or “exquisite corpse” approach, whereby each collaborator adds a new element to the story (a sentence, a paragraph, a scene, etc.), adding to but not altering what came before. This is typically done in a linear, forward-looking way:

Serial Story Collaboration

Another example is the parallel approach, which is more of a real-time, committee-based approach. A decades-old example of this kind of collaboration is the fictional television series, with a room full of writers hashing out ideas for the script, working together to craft the best possible show, episode by episode.

Parallel Story Collaboration

A third collaborative storytelling path is storyworld collaboration. In this process, the result is a collection of stories that share a common world and whose stories may be crafted by an individual or a group:

Storyworld Collaboration

This last example differs from the previous two in that the container of narratives is a world (populated by stories). In serial and parallel storytelling, the container is a story (populated by contributions that together form a single narrative).

[Note: Of the three kinds of collaborative storytelling, storyworld collaboration truly captured my imagination the most over the past several years. It’s been a source of interest and inspiration as I explored the challenges and benefits of bridging creatives and consumers (especially in a particular form of collaboration I call a shared story world).]

Now that we’ve drawn a general circle around the term, “collaborative storytelling,” let’s take a look at some of the major influences I believe affected the course of this form of narration.

A Century of Collaborative Storytelling

Until the Internet, it was difficult to quickly or easily collaborate as a group outside of highly localized attempts (and most collaboration used the serial approach due to the need for asynchronous and analog communications). Our always-on, always-connected digital age changed all that, and the result has been new ways to collaborate at both the story and storyworld level.

And it’s not just technology that spurred the amount of collaborative storytelling we’re experiencing. Over the past several decades, many factors contributed to the increased interest in collaborative storytelling. Let’s look at a few.

COMIC BOOKS

offered some of the earliest examples of collaboration at the storyworld level, with DC and Marvel heroes interacting within a common setting (usually Gotham or New York City, but both publishers lost little time expanding the scope of their respective shared worlds to include entirely new universes).

While individual titles were often created using a one-writer/one-illustrator team structure, the comic storylines eventually began to criss-cross each other, resulting in cameo appearances, alternate timeline scenarios, and limited run series of heroes temporarily teaming up for a common adventure. In some cases, previously stand-alone heroes were brought together to form teams with their own on-going titles (e.g., DC’s “Justice League of America” and Marvel’s “Avengers”).

Management of the increasingly complex universe of characters, histories, and plotlines forced DC and Marvel to occasionally reboot a title. This allowed them to reintroduce an existing character from scratch, jettisoning undesired legacy luggage (secondary characters, events, histories, etc.) from the previous titles. It also gave fans a chance to get in on a new title of a familiar character without the need to catch up on potentially hundreds of prior issues. Sometimes, secondary characters were elevated to primary protagonist status by displacing them chronologically or geographically (see DC’s on-again, off-again series, “Teen Titans”).

With literally decades of experience in collaborative storyworlds, the creators and readers of comics have provided all of us insights on the creative challenges and opportunities of sustaining a shared world of collaborative tales. In the process, entire generations of consumers have grown up completely comfortable with alternate timeline narratives and multi-threaded storylines.

TELEVISION

is a wonderful example of the parallel process of collaboration. Television sparked a new form of entertainment that allowed for serial storytelling but required a small team of creatives to hammer out weekly scripts for this visual medium. While one individual may have driven core story ideas, they rarely penned every word of every script. Instead, seasonal arcs and episode stories were batted around, stretched to their limit, rejected, resurrected, and put through a tortuous process with the goal of burning away narrative imperfections. This alchemical purification yielded story experiences unachievable by any single individual.

And given the on-going nature and potentially convoluted plotlines that could easily spill across several years, it was necessary to create a system to help maintain continuity. The “story bible” became the catchall phrase to refer to this repository of show knowledge (traditionally a document, but there’s no reason it couldn’t be an entirely digital system or online service). The bible was the go-to reference doc for the show, and as the concept matured over time, it was applied to other mediums like video games.

Television had another impact on collaborative storytelling: contributing to the advent of modern fan fiction. Certainly, the practice of using another person’s creations (whether to parody the original work or pay homage) has been around long before television, but most sources credit the show, “Star Trek,” for inspiring viewers to bring the practice to a new height.

Not only did Trek viewers write their own stories featuring the familiar cast of characters from the show, they added their own characters, starships, planets, and aliens. They wrote stories that would never have been commercially viable at the time (the most extreme form possibly being the “slash” fan fiction which derives its name from the convention of referring to same-sex romances by the names of the leading characters, as in “Kirk/Spock”).

Fan fiction writers knew they could never commercially profit from their creations, as they were using someone else’s intellectually property without permission. [note: For simplicity’s sake, I’m avoiding a discussion on the topic of “fair use” under U.S. law as a justification for the commercial use of another’s copyrighted work (e.g., when used for educational or satirical purposes). Yes, under certain conditions, fair use does provide for commercial use of another’s copyrighted work without permission. However, it’s a legal shield (i.e., defense) – as such, you’re never entirely sure you’re protected by fair use until you wind up in court, and by then it’s a bit late…].

Neither “Star Trek” creator Gene Roddenberry nor the show’s network, NBC, went out of their way to encourage the user-generated content. Still, most fans wrote their stories out of a sense of passion and personal enjoyment. Money and recognition by the powers that be simply weren’t driving factors.

“Star Trek’s” cancellation in 1969 after only three years did little to stem the interest of its fans in adding their own voices to the world Roddenberry envisioned. While Trek fans helped the starship Enterprise continue to boldly go where no one had gone before, another form of collaborative storytelling was gaining popularity. This form would come not from Hollywood but from humble beginnings in the Midwest.

TABLE-TOP ROLE-PLAYING GAMES (RPG)

, or as most would come to call it, “Dungeons & Dragons,” ushered in an entirely new industry and sparked the imagination of a whole new generation.

RPGs showed us how a small group of friends (or even strangers) could come together and, using an agreed-upon rules set, take on the personas of characters they created, experience pretend battles, go on dangerous adventures, and return home with treasures and tales…all in just a few hours and from the safety of a kitchen table. Little more was needed than pencil and paper, a few rules, some die, and a creative imagination.

A typical RPG evening involves one person (the game master, or GM) guiding the rest of the group through a story, with players pretending to be different characters in a fictional setting. The GM takes on the roles of the characters and monsters the players encounter during the adventure, giving everyone in the group the opportunity for both role-playing and improvisation. Although the level of narrative can fluctuate radically based on the GM and the players, I’ve personally played characters in RPG campaigns that spanned years (I’m talking real-world time, not in-world time). Those experiences were undeniably collaborative storytelling, and the most enjoyable ones always involve GMs who were gifted improvisationally.

And RPGs didn’t stay relegated to the fantasy genre for long. Science fiction, military battle simulations, horror, and mystery games sprung up, demonstrating how flexible the RPG system really was. Original RPGs worlds have crossed mediums as well, serving (not always well, I must confess) as the source content for video games, novels, card games, and movies.

By the late 1980’s, the RPG industry had essentially peaked but was far from over. And another new development was well under way that would affect collaborative storytelling almost as much as it would change the world.

THE INTERNET/WORLD WIDE WEB

connected to the world and placed the power of the global network in the hands of non-technophiles.

Although originally launched in the 1960’s, nearly two decades later the Internet was still primarily used by academic institutions and a small group of tech-savvy users who wanted to “go online” and connect with others around the world. This interaction was initially limited to email and discussion groups, and it was further hindered by the text-only user interface (users could send each other pictures, but they had to be downloaded to local computers in order to be viewed). It took the development of the computer protocol, HTTP, and a graphical program called a browser to let the world understand the true capabilities of this global network now often referred to as the (World Wide) Web.

The Web essentially introduced the Internet to non-technical people around the world and sparked an unbelievable infusion of money and creativity (Whatsapp, anyone?). The Internet put an amazing amount of power directly in the hands of everyday people, and they took advantage of it. Information flowed, free services sprang up, and the Internet became a tool of communication on a massive scale.

And the architecture of the Web helped spark a new way of looking at information, too. Up to then, we typically consumed content in a very linear way. You watched a TV show from start to finish. You read a book from start to finish. You played a game from the beginning until the end (i.e., a “win” condition is reached).

The hyperlinked approach of connecting content on the Web meant that consumers had the power to jump around when and where they liked, hoping from website to website as they liked. It also meant creators could construct multimedia and interactive experiences where audiences could jump in at multiple entry points.

Or, to put a philosophical filter on it, what is the first “page” of the Web? Where does the Internet “end?”

And what does a globally connected community like to do? If history is any indication, create content! From a macro point of view, the Web could be viewed as a massive experiment in collaboration – we have all been laboring for years, contributing to this ephemeral thing called the Internet.

From a micro point of view, we need look no further than Wikipedia as a perfect example of this new mindset. Working together and without pay, strangers from around the world add their knowledge and thoughts to a dynamic, online database of content that is available to the public for free. This crowdsourced resource is constantly updated, edited, and revised around the clock by volunteers who attempt to maintain accuracy and objectiveness of entries and properly link related Wikipedia pages.

And Wikipedia pages of content are linked to and from multiple points. A Wikipedia entry on airplanes may have a hundred links to other related Wikipedia pages (e.g., principles of aerodynamics, balloons, helicopters, the Wright Brothers, forms of propulsion, various parts of a plane, etc.). Because of the hyperlinked format, you could spend years clicking your way through Wikipedia, hopping from one page to another and never leave the Wikipedia.org website.

So, while Wikipedia isn’t a story per se, it’s certainly a collaborative endeavor where contributors can jump in at any time and on any page. And the idea of collaborative storytelling using a similar framework didn’t take long to emerge.

Sites like Wiki Story provide resources for this kind of joint narration, and there are countless other sites with similar functionality:

A recent platform – AuthorBee – piggybacks on Twitter, allowing users to initiate as well as contribute to stories told one tweet at a time. Nimble almost to the point of being ethereal narration, it’s a great example of a light “meta” service used to craft collaborative narratives by re-purposing the functionality of an existing service.

It’s anyone’s guess what the Internet or the Web will look like in a decade, but rest assured, it’s still just a guess. We tend to be very bad at extrapolating future outcomes, mostly because the future depends on things that may not have happened yet. One prime example: technological developments…

TECHNOLOGY

advances are not limited to online services. Smart phones and tablets are extending our ability to connect, create, and collaborate in increasingly ubiquitous ways. While it would be a stretch to label social media as a story in the traditional sense of the word, our growing comfort with constant communication is helping encourage a default mentality of online, interactive conversations. That’s not really surprising, given that the Internet was originally designed as a communication device to shuttle information between networked nodes.

Given the increasingly digitized and mediated backdrop of our society, the changes in consumer behavior and mentality regarding content is likely to support additional experimentation with new forms of collaborative storytelling. In a matter of minutes, a single individual can put together a multimedia experience using a computer costing as little as $300 and share it with the entire world. Given the market saturation of computers and the percentage of individuals already connected to the Internet, this represents a new level of audiences’ ability to participate in entertainment properties.

None of this was even on the horizon a few decades ago.

And if fandom is any indication of the desire of audiences to jump into the entertainment properties they love, look no further than the “Harry Potter” franchise for eye-popping proof. The combined word count of the seven Potter novels is roughly 1,000,000. The FanFiction site currently lists over 660,000 fan-written stories set in the world of Harry Potter.

That’s a words to works ratio of over 2 : 1.

Consider that. An entire story has been written for every two words published in the JK Rowling’s series. And that’s just the stories available at FanFiction.

Okay, so, it’s clear that as a society, we’re increasingly not just comfortable with the idea of joint authorship, we’re actively seeking ways to collaborate in all kinds of mediums and across all kinds of platforms. The forces of technology and consumer behavior have been molding our attitudes about storytelling for quite some time.

But what does this all mean? What does collaborative storytelling look like in the 21st century?

Recent Examples of Collaborative Storytelling

As the factors fall into place to encourage collaborative storytelling, what kind of projects can we expect to see? What will they look like? How will they work?

While the details may vary, based on the larger and longer-running collaborative projects in recent years, the future ones won’t be limited by mediums, platforms, or money.

I’ve been archiving examples of what I call shared story worlds for a couple of years now, but there are plenty of others to examine.

The “Heroes” Create Your Hero Contest

NBC ran a campaign for its “Heroes” television show, allowing fans to vote on a series of attributes that would be used to define new characters for the “Heroes” world. The resulting character appeared in the official online “Heroes” comic, which focused on the television show’s secondary characters, exploring their backgrounds and stories in more detail.

1632 (Grantville Gazette)

The alternate timeline world of 1632 began as a novel written solely by Eric Flint, but within a few years, 1632 became a shared world on many levels. First, Flint invited a handful of writers to help him explore the world. Several sequels and related works were published by established writers like David Weber, Andrew Dennis, and Virginia DeMaurce (some of the novels were written collaboratively while others were written by a single author). Additional publications for 1632 included anthologies.

But Flint went one step farther when he invited fans to submit their own stories for review by a collection of professional writers. An ongoing series of fan fiction anthologies is now published under the title, “Grantville Gazette,” and its content is given the same canonical and continuity editing as the other titles in 1632 . Fans are paid for accepted stories, and their works go through a professional editing process before winding up in a Gazette that’s sold to the public.

Bar Karma

Best known for his ground-breaking video games Sims and Spore, Will Wright applied his own ideas about collaboration to his collaborative television show, Bar Karma. Hosted on the former Current TV website, Bar Karma allowed anyone to contribute to the show’s production, including suggesting story ideas, scenes, scripts, costume and prop ideas, and marketing recommendations. Participants were able to vote and comment on each other’s submissions, and while the creative team behind Bar Karma made the final call, it carefully weighed the input of the show’s fans.

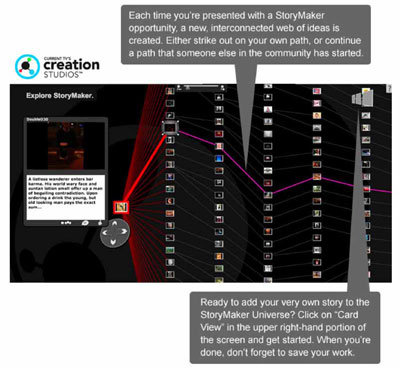

Perhaps most intriguing about the process is Storymaker, the custom software program Wright created to handle the collaborative process. It tracked submissions, plotline and narrative paths, stored uploaded content, and provided a graphical interface to ease navigation through it all.

Storymaker Software Screenshot

While “Bar Karma” failed to catch on (it ended after one season), I suspect the information gleaned from Storymaker was far more valuable than anything the show produced. In fact, you could almost posit that “Bar Karma” was simply an excuse to build Storymaker and learn about habits of collaborative storytelling (knowledge that would be useful in other endeavors, say, video games – something Wright has been known to dabble in).

Tiki Wiki Fiki

While many of the examples archived at Shared Story Worlds have a massive amount of time invested in them, launching a shared world can literally be done in a matter of minutes.

Case in point: Tiki Wiki Fiki, the brainchild of a man most mad, Flint Dille. This world got its start a few years ago with little more than a “let’s just do this and figure out the logistics later” attitude. In fact, it was born not from weeks of careful planning or detailed world building but rather a painting, a crazy mashup of Polynesian culture, Nazis, and pulp that landed in Flint’s Facebook stream.

Rather than making a brand new world, TWF bootstraps itself on a confluence of known tropes, making it easy for audiences to jump in. Best of all, the “world” of TWF is built on a foundation of public domain material, but plenty of copyrighted materials has positioned audiences to step into the TWF world.

There’s very little in the way of a world bible, and as it’s a sideline interest for Flint and his audience, the pressure to force its development is non-existent. Contributors are there when they like, as they like.

This is perhaps an extreme example of collaborative writing, a lean approach on the bleeding edge, but one which has managed to survive (perhaps because it’s so low-maintenance). Submissions are handled as they roll in, and the only marketing is Flint’s use of social media to occasionally remind his network of TWF.

More Encouraging Signs for Future Collaborative Storytelling

These are just a few examples of collaborative worlds, but a far more compelling case for the rise of collaborative narration can be seen in the number of platforms being created to support not one but many worlds. These back-end engines and services are striving to help content producers create structured spaces within which audiences are invited to explore, collaborate, and contribute.

Angry Robot Books’ Worldbuilder

Concurrent with the 2012 release of Christopher Smith’s “Empire State” novel, Angry Robot Books launched Worldbuilder, a platform for inviting and encouraging fan contributions within the novel’s setting. Angry Robot Books then applied the Worldbuilder framework to “Empire State,” set up a dedicated “Empire State” site for submissions, and began curating contributions (which were published under a Creative Commons license).

Amazon Kindle Worlds

Perhaps most notably was the launch of Amazon’s Kindle Worlds, the biggest example of a shared story world framework when measured by the kinds of worlds it opened up to fans: “Gossip Girl,” “The Vampire Diaries,” Hugh Howey’s “Silo Saga,” “The Foreworld Saga” (Neal Stephenson, Greg Bear, et al), and more.

If your submission is accepted, you’re allowed to sell it via the Kindle Store and keep the royalties (a similar exercise occurred with the “Hunger Games” movie release, when Lionsgate allowed fans to apply pre-approved images to CafePress products, sell those products through CafePress, and retain the royalties).

Theatrics

![]()

Theatrics has served as the back-end engine for several interactive experiences. In these cases, interaction is a bit of an understatement. Audiences actually create content and contribute it to the experience, usually affecting the larger story. There is often a call-and-response structure, where the experience designers publish a piece of content or request content from the audience, who then respond accordingly.

For example, one of the Beckinfield videos produced by the designers invites audiences to respond to an unusual event in the town of Beckinfield – in this case, it was a power outage during a local football game. Contributors created their own characters or personas within the Beckinfield world, then posted videos in character, giving their responses to and explanations of the phenomenon (in some cases, they even critiqued or “corrected” the statements of contributors).

What This Means for Content Producers

These examples highlight some of the possibilities for collaborative storytelling and participatory entertainment, but there are an equal number of challenges to effectively managing these kinds of projects.

CREATIVE QUESTIONS

On the creative end of the spectrum, the mechanics of collaboration have to be designed, communicated, and supported.

- Is there a tight control on what’s official?

- Is there a strong emphasis on maintaining world continuity, or will conflicting pieces of content be allowed into the property?

- What resources are necessary for the collaboration (do you need to build your own Storymaker or use a platform like Theatrics?)?

LEGAL QUESTIONS

On the legal side are a host of questions about which content is allowed and under what conditions may content be remixed.

- Who owns the copyright to the contributed content – the world owner or the contributor?

- Who (if anyone) can monetize contributed content?

- Can collaborators use each other’s creations (e.g., characters, places, items)?

- If so, under what conditions?

- Is there a revenue sharing component to the collaboration, and if so, what are the rules for how revenue is shared (especially if collaborator A remixes collaborator B’s character)?

- How will world owners maintain a clean chain of title across their world and the individual works (e.g., if they hope to license out some/all of the content)?

- How can these issues be addressed without having to resort to costly legal services?

OPERATIONAL QUESTIONS

In between the creative and legal questions are the logistical concerns.

- What mediums will be used and how will the content be submitted, edited, and posted?

- How will the editing process work?

- What tools, services, and resources will be needed to support the editing, production, and publication processes?

- Given that the project audience includes both consumers of content and contributors of content, how will the marketing for those two segments differ?

- What countries or global markets will the collaboration take place in?

- What limitations on contributed content will be enforced (e.g., must be in English, contributor must reside in Australia, etc.)?

for more about SSW design considerations, please see my Shared Story World Design Primer

Despite all of these challenges, more examples of collaborative storytelling appear daily, with an increasing emphasis on participatory storyworlds, where the end product is a crowd-sourced intellectual property consisting of content created internally by employees and work-for-hire contractors as well as externally by audiences, fans, and consumers.

Most SSWs fall outside mainstream Hollywood and explore the spectrum between traditional entertainment (i.e., the creator owns all copyright, trademark, and commercial rights) and pure hobby-style entertainment (i.e., the participants don’t own the intellectual property and/or there are no opportunities for the participants to commercialize their contributed works).

It is highly unlikely that most entertainment properties of the future will be SSWs, but it is very likely that the level of participation and contributions of audiences will continue to rise. I believe the likely outcome is a mix of collaborative storytelling experiences.

For example, smaller, lower-budget SSWs tend to be more open, inviting audiences to jump in a large part of the world, whenever they want, and through a variety of mediums. Larger, higher-budget properties usually employ tightly controlled sandboxes, where audiences are given a much smaller set of content to use, have more restrictions placed on when/how they can participate, and may be limited to certain mediums.

As the more experimental and innovative SSWs evolve over time, best practices and lessons learned will migrate towards the Hollywood end of the spectrum where they can be applied to larger budget properties.

Whatever the future of collaborative storytelling is, one thing is certain: we’ll be exploring it together.

WOW—here it all is, laid out in one handy post. You’re the king of shared story worlds, Scott! I appreciate the history as well as the look ahead and the list of tools. Comic books as giant collaborations (ever-evolving)—that’s so true, as the characters and plot lines spill out of the pages into various other media, reincarnated, remixed, and re-imagined.

Thanks, Lorraine! The good news – for creatives and audiences alike – is that the tools and techniques will continue to evolve. So many possibilities…

Hi, Scott.

It’s a huge work about collaborative creation.

In Europe, the authors have only existed since the Middle Ages. Before that, stories, mythologies, tales were transmitted only orally.

And I do not speak of the Celts and Saxons who did not use writing, or very little.

Most (all ?) mythologies are based on collaborative work.

Collaborate, is a sort of homecoming

So true!

I only skimmed the surface, and I focused on only some of the major factors in the past one hundred years. There’s SO much more, but I had to stop after 4,000 words. :)

Wonderful Scott! I think my favorite “collaborative storytelling” or “shared storyworld” is Luther Blisset.

That. Is. Awesome.

Thanks for pointing me to Blissett!

What an excellent, thoughtful post! Thank you! (off to share it with the world)

Glad you enjoyed it, Aaron, thank you (and I’m now embarrassed I never mentioned LARPing…well, I did say it was non-comprehensive)!

Interesting overview, congratulations! I am currently researching about creative models of collaborative storytelling and co-creation for my PhD. Many of the examples that you used here are case studies in my dissertation. You’re right, new projects and tools are coming. The present/future of collaborative storytelling is evolving very fast!

José – sounds like you’re having a lot of fun with your PhD research! Best of luck with it, and thanks for stopping by and commenting!

Excellent post. This is sometimes so hard to explain without talking about the evolution and you have done it so well. Thanx.

Thank you, Laurinda!