In which my attempt to forge a new creative path led me right back to an old one.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of being invited to co-teach The Art of Visual Storytelling course at the prestigious Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA. I’m three weeks in to this semester’s class and loving it. Plot wrangling! Story structure! Wordsmithing! All the narrative nourishment a typing monkey could hope for.

But as this course focuses on visual storytelling, it wound up bringing together two things I’ve long been interested in.

How’s that, you ask? Allow me to explain…

From Ewok Villages to Art Center

I drew a lot as a kid (okay, I even admit to drawing a lot as a teen-ager in high school, including mapping an Ewok village on graph paper during Physics, which says more about my Physics teacher than it does about my interest in Physics).

However, for reasons that still elude me, I don’t remember ever expressing a desire to sign up for an art class, much less actually taking one.

By college, my doodling days were over, and I spent my time doing what all teenagers in the late 1980’s were legally and ethically required to do: consume massive quantities of media.

None of that was a problem, per se, as I had developed an early love for books, movies and television. That love simply expanded under the explosion of chain bookstores and this new-fangled technology called cable television.

In college, it was even more of the same in that regard.

I was already reading quite a bit for school and pleasure (Shakespeare, Hemingway, Alan Watts, Michael Moorcock, etc.), and I followed Nielson’s recommended minimum intake of television content (Moonlighting, The Tracy Ullman Show, Miami Vice, It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, Star Trek: The Next Generation, The Young Ones, Kids in the Hall, L.A. Law, Thirtysomething, Pee-Wee’s Playhouse [side note: this required wearing pajamas and eating sugary breakfast cereals in front of the large screen TV in my dorm lobby with other PWP aficionados], MTV’s 120 Minutes and, of course, Late Night with David Letterman).

We all know every growing boy needs his media meals to be well-balanced, so I also adhered to the MPAA’s definition of a well-balanced movie diet (Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, Gandhi, Aliens, Batman, The Breakfast Club, Predator, Ferris Beuller’s Day Off, Die Hard, St. Elmo’s Fire, Pretty in Pink, Robocop, Platoon, Indiana Jones and Last Crusade, A Room with a View, Dead Poets Society, Lethal Weapon, Big Trouble in Little China (you DO know about the latest board game, right?), Rain Man, Say Anything, Christmas Vacation, Wall Street, Real Genius, Brazil, Parenthood, When Harry Met Sally, Steel Magnolias, Moonstruck, Better Off Dead, Uncle Buck, Dangerous Liaisons, Hannah and Her Sisters, Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Out of Africa, Bull Durham, Nothing in Common, Less Than Zero, Peggy Sue Got Married, The Money Pit, Baby Boom, The Sure Thing, About Last Night, She’s Having a Baby, Scrooged, Babette’s Feast, Barfly, Radio Days, 84 Charring Cross Road…wow, that was an awesome few years of movies!).

I switched majors in college from computer science to creative writing, but you have to remember this was early 1986. The World Wide Web was still nearly a decade away, the Internet was primarily text-based email addresses at universities around the world, and even dial-up connectivity was just beginning to make its way into consumer’s homes. One glance at the guys behind the mainframe computer window at the lab was all I needed to take a hard pass on a Comp Sci degree if that was my future. No pocket protectors and super-loud computer labs for me, thanks!

I worked full time for a year before returning to college for a second degree, this time a B.A. in Religious Studies. I focused on Zen and Taoism, and my plan at the time was to teach comparative religion in college. Life had other ideas for me – a LOT of them – and none involved me teaching. Back to the non-academic work force I went.

[side note: Ironically, I wound up right back in the same field I initially fled – computers. By the time the World Wide Web had turned the Internet from a text-only toy for academic researchers into the mainstream superhighway of porn information, I was running Unisys mainframes, administering a Windows 95 PC network, and building Lotus Notes programs. Some fates you just can’t shake…]

The decades rolled by, and I dutifully maintained my role of content consumer. Writing consisted mostly of annual Christmas cards, and that dream of learning to draw remained just that.

In the mid 2000’s, though, I had an idea for a fantasy story set in a world inspired by medieval Japan and pulling from a lot of the Shinto religious practices I had learned about from my second B.A. Finally, the mental rust covering my creative gears began to flake off as ideas started bubbling up. I took a few tentative steps at fiction which were accelerated by a media venture I co-founded in 2008 called Brain Candy, LLC (something I’ve touched on in past posts).

A few years after starting Brain Candy, the arc of convergence between my love of art and words began to present itself as I discovered the increasing amount of art and art tutorial videos online. DeviantArt and YouTube were regular go-to sources of inspiration for my writing. I discovered some of the art I grew up on, like the Star Wars blueprints, had been labelled into something called “concept art.” And I loved it.

But the convergence of my writing and drawing passions hit critical mass when I had the fortune of meeting Orrin Shively.

Orrin’s an Art Center College of Design graduate and part-time instructor, as well as a former employee at Disney and Universal (25+ years in park and experience design). Orrin’s knowledge of art and design is distilled from decades of hands-on experience.

After learning of my love for concept art, Orrin began inviting me to the various open houses and grad shows Art Center hosts each year, and I found myself increasingly impressed with the idea that learning to draw was, perhaps, not as much of a forgone conclusion for this forty-something-year-old as I had come to believe.

[side note: My first actual experience with Art Center was at a friend’s birthday party held on the rooftop of the Art Center South Campus building before I met Orrin. As I was guided up to the party by an AC employee, I mentioned how impressed I was with the facility. She offered to give me a brief tour and provided a helpful hint about their evening program, Art Center at Night: it’s open to anyone, no need to apply for enrollment in a degreed program. Walking the halls and seeing the art on the walls left me very intrigued about returning to the classroom. By the time Orrin pointed me to Art Center, I was beginning to suspect the coincidences were not so coincidental.]

Each visit to the main Art Center campus left me wondering: could I jump into this world? Could I achieve even a modicum of quality in my art? Even more intriguing: could I improve my skills enough to feel comfortable sharing them publicly as a visual extension of the stories rattling around in my head?

I began to hope so.

Google searches were turning up a constant stream of new content around drawing and increasingly around concept art. I found a handful of great artists posting videos on YouTube, in particular Sinix and Sycra. I loved their positive “you can do it, too!” comments as much as I did their artistic styles and guides.

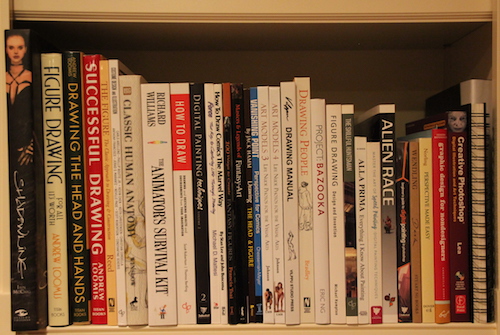

I started buying books on drawing, too.

I wasn’t actually drawing a lot, mind you, but I began internalizing a bunch of fundamental concepts and kept up a constant flow of inspiration from DeviantArt.

After two years of popping into Art Center to see what was possible, enjoying the intermittent inspiration generated after wandering the halls, and being surrounded by amazingly creative art, I decided enough was enough. I could either keep surfing DeviantArt and admiring other people’s work, or I could get off the sidelines and into the art game myself.

And so I did.

The Hopeful Artist

In the spring of 2013 I signed up for Pencil Kings, an online tutorial site. It was somewhat new then, but it has grown a lot since (FYI: the site’s founder, Mitch Bowler, could not be a nicer or more positive guy!).

At around the same time, Orrin suggested I look into the Introduction to Entertainment Design course at Art Center at Night. Then he pointed me to one of the instructors, Eric Ng, who also happens to be an Art Center alum as well as a former student of Orrin’s.

I met with Eric in the early spring of 2013 and asked about the course, solicited guidance on supplies, and tried to determine if I was capable of leap-frogging the prerequisites and jump right into Eric’s course. With some encouragement from Eric, I signed up.

Then the fun began!

I bought yet more books on drawing and art (thank you, Amazon Prime, and big props to Stuart Ng Books in Torrance):

Finally, I turned my attention to supplies.

I learned about the various types of pens, pencils, and markers. I discovered just how diverse the different drawing pads were (digital and analog). I visited Blick’s and Swain’s and experienced the rush of walking down aisle after aisle of art supplies (“whoa, a calligraphy brush! pencils in every conceivable color! markers categorized as ‘light’ and ‘cool!’ notebooks and pads in every size, shape, and dimension!”).

[side note: despite Eric’s assurances that I really only needed a notebook for sketching and at most a handful of pencils, pens, and markers, I went overboard; most of my supplies haven’t been touched since I bought them, but they certainly look impressive!]

In short order, I assembled a box of supplies and impatiently waited for the first session of the class.

It felt an awful lot like the first day of elementary school.

I arrived nervous and excited and very unsure of myself. Just how embarrassing was this going to be for me? Was it a mistake to jump into an advanced class without any training (formal or self-taught)? Would I be the kid everyone else either made fun of? Or, worse, pitied?

In the end, I didn’t care.

I wasn’t in the class for a grade – I was there to learn. I was going to squeeze as much as I could from that class and soak up every bit of knowledge possible. I didn’t care what the other students thought, and I only had one goal: leave the course a better student that I started.

Improvement was the only benchmark for my success.

Eric turned out to be a quiet but humorously gentle giant who demonstrated both patience and encouragement with every student. Looking back on it now, I realize he met every student wherever they happened to be on the talent spectrum and did his best to move them along. That’s not as easy as it sounds.

Eric ran the class primarily with a focus on group-level critique and in-class demonstration. The first half of each class was peer review of that week’s homework, which meant everyone’s art went up on the wall for group critique (yikes!). The second half was a lesson/demonstration by Eric.

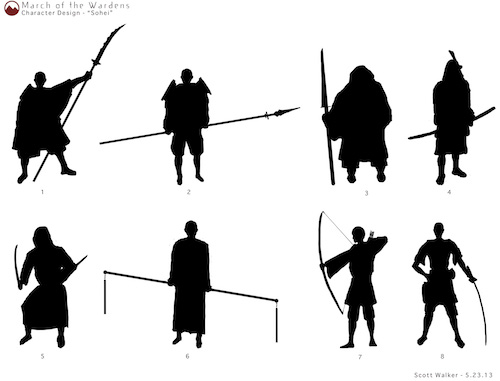

He challenged us to create a world we wanted to play in, then gave us a lightly structured story framework to follow as we developed our characters and settings. I called mine “March of the Wardens” and adapted the medieval Japan story I was working on.

Over the 14-week course, we developed finished pieces of art for the various parts of the story: character design, props, vehicles, interiors and exteriors, and even an original movie poster. At the last class, we “pitched” our development idea using our story summary and art.

I came home wired from every evening class, and it would take a few hours to finally wind down before getting to sleep. Little did I realize how unique that kind of experience could be (more on that shortly).

Interestingly, I began noticing several similarities between storytelling and artistic techniques. Eric’s weekly advice on topics like composition, symbolism, and layout evoked storytelling equivalents I had known for years. There’s a limit to how much overlap these two practices actually have, but I was intrigued by how much common ground they shared. I filed that observation away under “Review Later.”

In all fairness, my experience in the class wasn’t strictly butterflies and rainbows.

Just as I started to feel like I had a tentative grasp on characters, off we went to props. A week later, we were doing vehicles. Then we spent a week learning how to use the free Sketchup program to mock up 3D digital models for our interior and exterior compositions (Sketchup is an immensely helpful tool for creating layouts in perfect perspective).

I loved the broad exposure of the class, but it’s difficult to dive deep into an area when every week brought a new topic and challenge. The phrase “drinking from a fire hydrant” cropped up repeatedly in my thoughts as I tried to stay on top of each week’s homework assignment.

And having skipped some of the fundamentals like perspective and figure drawing, I really struggled with my assignments. Clearly, I was in over my head, and taking another advanced course without getting a handle on the basics seemed foolish.

Yet even that realization did nothing to dampen my take on the ACN experience. I finished the class excited and enthusiastic about circling around to get a solid foundation under my fledgeling feet.

Body of Work

So, in 2014 I took a figure drawing course at Concept Design Academy, also in Pasadena. I couldn’t find a figure drawing course schedule at Art Center that fit my own schedule, so I opted for one at CDA.

That course turned out to be a completely different kind of experience from the one at ACN.

We’d spend the first thirty minutes or so warming up with 5 and 10-minute poses, usually with a live nude model as the reference. During that time, the instructor, Kevin Chen, and his TAs would walk around, giving one-on-one feedback. Then Kevin would deliver a lesson/demonstration, usually focusing on a particular part of the human anatomy. We’d finish the class with a few more sketches on our own.

No homework on walls. No peer-review feedback. No cool concept artwork.

Just me, a large pad of newsprint, and a charcoal pencil.

It never occurred to me art classes could be so incredibly different in format.

While I reveled in the entertainment course, the figure drawing course began to feel like a grind. My lack of talent was impossible to hide, and I discovered the same inner editor who enjoyed criticizing every word I wrote apparently found equal enjoyment in criticizing every line I drew.

How hard is it to draw something barely more complicated than a stick figure in proportion? Pretty hard, as I soon learned:

I think the students at CDA were as similarly talented as those at Art Center (in fact, I learned many art students bounce around between different schools, especially if they aren’t aiming for a degree), but the lack of peer review and the subject matter affected my impression of the course far more than I ever expected.

The lack of any kind of structured or forced peer-level interaction meant I mostly showed up on my own, sketched on my own, and went home alone. Chen encouraged us to get together outside of class – encouraged anything to help us stay energized about our progress – and CDA offered drop-in, unguided sessions Sunday nights where a nude model would pose for a few hours, giving you the chance to improve your skills between classes (which I did manage to hit once or twice).

But in this case, I didn’t need anyone to tell me how awful my sketches were. I knew that already. I carried the evidence in my newspaper drawing pad to class every week. What did I need?

Apparently, the interaction with, and feedback from, other students. I had really pleasant, consistently positive interactions with the other students in the figure drawing class, but the subject matter and class structure made it more difficult to build the same kind of relationships I had at ACN.

At CDA, many students kept their drawing pads covered, and no one put their homework on the classroom walls (we had the option of posting them online in a private group, but few students did that consistently; those who did got almost no peer feedback). The few times other students were kind enough to show their work to me, I was humbled. Big time.

Surprisingly, sketching nude figures got to be boring, despite some of the models being very attractive. The human body is amazingly beautiful, but I missed seeing costumes and props and vehicles and landscapes. I missed getting lost in and inspired by concept art, having my imagination fired up by new possibilities.

And since we weren’t focusing on anything except the human body, even when I did work up the nerve to interact with another student, the conversation went something like this:

Me: “Wow, that’s a really good arm!”

Other CDA student: “Thanks.”

<sound of crickets>

In Eric’s class, I eagerly waited to see the other student’s work on the wall. Everyone had their own style, and there was a diversity of genres (fantasy, science fiction, contemporary, magical, etc.) and content (spaceships, castles, mountain lakes, deserts, tanks, aliens, priests, turtles, blasters, boats, restaurants, etc.).

I could ask about inspirations the other student had for their vehicles, inquire about how they achieved a particular lighting effect on their props, dig into the characters and background of the students’ stories.

None of that was possible with the figure drawing course.

Me: “How did you get the muscles in that leg to look so real?”

Other CDA student shrugs: “A lot of practice.”

And there it was.

Perhaps the real struggle I was facing wasn’t the course structure but rather my own shortcoming of not doing the hard work. Not putting in the necessary consistent practice.

As Orrin is fond of saying, art is more about the miles than anything else. Writing is, too.

The ubiquitous “they” say half of success is showing up, and while I was showing up for class and my homework, I was just doing the minimum. Of course, when you’re working full-time, married with three kids, on the board of a charity, etc., the minimum can be very minimal indeed. But if that’s all you’re doing, how fast is your progress going to be?

Even as I acknowledged my lack of drive, I couldn’t ignore the huge difference I felt between the ACN class and the CDA one.

ACN: “Whoo-hooo! You finally made it, Scott, awesome, grab a pen and some paper, and let’s have us some fun! Who cares if you’re just starting out, you can hide all that lack of talent behind a truckload of enthusiasm! Swords! Spaceships! Aliens! Demons! Wheeeeee!”

CDA: “Party’s over, pal, the real work begins now. It’s just you, a pencil, some paper, and a nude dude standing in the center of the room. Now this is super simple, nothing complicated. All I want you to do is draw a stick figure with the proper proportions. Try to make it somewhat resemble the guy over there. Think you can handle that, champ? ‹looks over my shoulder› Guess not.”

I need to very clear here to avoid any misconceptions.

Comparing Entertainment Design to Figure Drawing is an apples-to-oranges exercise. My guess is ACN’s Figure Drawing course is very similar to CDA’s. I’m not criticizing CDA, Chen, or the students in my Figure Drawing class. The only negativity I encountered was my own self-criticism and my surprise at how much I missed the social exchange from peer reviews and the concept art.

And I’ll confess I was disappointed to learn I didn’t have as much drive to master the fundamentals as I knew I should. Maybe I did try a short cut to art via the Entertainment Design course. Maybe I was paying the price for my impatience.

Still, I had gotten through two art courses and felt I had at least taken a few steps on my journey. I had a good handle on how the ACN program worked, I had found at least another good local option for courses if the ACN schedule didn’t work for me, and my desire to master art was slightly dimmed but no where near extinguished.

Which is why I was so eager to entertain Orrin’s invitation to co-teach a course at Art Center.

An Offer I Couldn’t Refuse

In late 2014, Orrin suggested we propose a new course for ACN’s offering. We kicked around a few ideas and eventually settled on one called The Art of Visual Storytelling, which wound up being 75% about art and 25% about story.

Sounds simple enough, but what would the course look like? How could I hope to teach artists the fundamentals of storytelling in a way they could directly apply the lessons to their art? What would the “deliverable” of the course be?

For the story portion of the course, I selected Christopher Vogler’s customized and slimmed-down “Hero’s Journey” structure to be the guiding text for the storytelling portion of the class, knowing that most of the students would struggle with creating a coherent story outline as much as I struggled with figure proportions. Then I went a step farther and crafted a generic but tighter outline based on Vogler’s model and incorporating lots of actions sequences to make the students’ art a little easier to access and explore.

I spared the students any reading and simply gave them a rough outline with generic actions sequences (e.g., “the hero is betrayed by the person they thought was an ally”). The students would lay their specific story on to the generic sequence and make it part of their unique tale (“David’s martial arts teacher steals the golden necklace and pushes David into the pit, leaving him to die.”).

For the art portion of the course, Orrin proposed having the students create a keyframe image for each of Vogler’s twelve plot points (or stages). He would provide guidance on layout, design, construction, etc.

In the end, we settled on a schedule that allowed me to front-load my storytelling lectures so the students could lock their stories as soon as reasonably possible. After that, they could focus full-time on their art. As with Eric’s class, we’d have peer-review every week, too.

The students would, at the end of class, orally present their original story to the class, walking us through it with visual aids such as storyboard keyframes for each of the twelve plot points, character design lineups, maps, etc. It seemed a good variation on what clearly was a tried-and-true formula from Eric’s class at ACN.

As expected, I love the peer review portion of the course, especially getting Orrin’s insightful take on the keyframes. I have attended three different universities and obtained three different degrees (I picked up an M.B.A. from USC in the early 2000’s), and I’m firmly convinced the most valuable aspect of learning is the in-room exchange, both between instructors and students and between students themselves.

Whenever a student makes an astute observation about another student’s work, I silently shout encouragement. Critiquing others’ work – much like what happens in a reading group for writers – often forces you to be a better creative yourself. It also helps hammer home guidelines that some of us consistently tend to forget.

And I was super excited to formalize my thoughts about the intersection of storytelling and art. Writing the lectures, finding art references, and organizing the information I wanted to share helped me identify weak areas in my own thinking, as well as introduce me to new ideas I hadn’t even considered.

That learning didn’t stop when I stepped behind the lectern and became the instructor, either.

What I Learned Teaching Visual Storytelling

I ended up learning as much about teaching as my students did about storytelling, perhaps even more. I suspect that’s often the case.

Here are some highlights:

1) Literary Techniques Through the Artistic Lens

As I dug deep into literary techniques that have an artistic equivalent, I discovered some seemed like good matches but ultimately weren’t, while others that initially looked difficult to apply wound up making for great in-class discussion.

For example, literary point of view seemed a natural fit for an art class. It’s literally the same term! But explaining the difference between omniscient third-person, limited third-person, second-person, and first-person truly paled in execution. That lecture landed with all the gracefulness of a drunk dodo and the appeal of a ten-day old banana peel. I removed it pretty early from my lecture deck.

On the other hand, a lecture based on a previous post of mine entitled Math, Magic, and Storytelling Shell Games ended up generating a lot of discussion as I steered the class towards Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics book and then presented the class with several pieces of art before asking them to tell me what they believed was happening based solely on the content presented in the work.

I challenged several of their presumptions, forcing them to justify their answers with objective analysis and critique of the art instead of taking their initial take at face value.

Conclusion: much like writing, you often don’t know what you have until you show it to someone else.

2) It’s About the Art, Stupid

There is a reason the students are in an art class at an art school and not in a writing class in an MFA program. They are, first and foremost, artists.

While many really dug into their stories and some even cranked out full-on treatments, others never seemed to enjoy the process. Or they wanted to but struggled. Or, in the case of one student, they turned in a first draft, ignored my feedback, and never revised it.

Eventually I realized that while I would love to have every student expand and explore their story, the narrative is really a means to an end. This isn’t a course about storytelling. It’s about telling stories visually.

I reluctantly started to curb students from going to far and spending too much time on their stories, painful as that was. Sure, they could continue revising their story weeks into the course, but at some point, revisions would force them to create new keyframes, too.

The sooner they locked down a story that worked well enough for the purposes of the course, the sooner they could bear down on making their keyframes shine.

Conclusion: sometimes good enough truly is good enough, and that’s okay.

3) “My Kingdom For The Perfect Story Structure!”

Vogler’s model is fine, and it clearly fits many a literary and cinematic masterpiece. But if I had to pick a story structure format that suits me to the bone, it would be Larry Brooks’ Story Engineering.

I wanted to use Brooks’ model, but I felt a reference to The Hero’s Journey (if I mentioned Bill Moyer’s PBS interview with Joseph Campbell, would I be dating myself?) and its well-known connection to Star Wars would be a more common touchstone for the students.

I’m also a firm believer that the more limits you place on a creative, the more creative they will be. As a result, I took Vogler’s model and drafted an even tighter story structure for the students to follow, in the belief that the fewer choices they had (read: the smaller the canvas), the easier it would be for all of them.

It was not to be, though the reasons varied from student to student.

Some students struggled with my “easier/more limited” template than others, and their struggles reminded me of my own challenges at mastering the deceptively simple technique of proper proportions for figure drawing.

I’ve tried a few different methods for figure drawing, and, frankly, some were better than others. But none seemed to be the perfect fit for me.

Conclusion: there is not a single story structure that will work in all cases for all student for all stories, but I still believe my modified Vogler’s template is the best bet for most of them.

4) Old Teacher Is Old

My attempt to use cinematic examples as an introduction to story structure betrays my age. I pull from a variety of genres across almost eighty years of film (Finding Nemo, Aliens, Star Wars, Casablanca, The Matrix, The Wizard of Oz, etc.), but even after overhauling and updating my lectures for subsequent course offerings, it’s clear many of my examples resonated only with a small group of students.

Conclusion: I am not as hip as my students, nor will I ever be. And that’s probably as it should be. : )

5) My Artistic Arc (a personal observation)

Everyone’s creative path is unique, and mine’s no exception.

I clearly prefer in-person classes, especially ones that incorporate peer-review components. Happily, I live in Los Angeles and have lots of options in that regard, but if I didn’t, I think online resources like Pencil Kings would be higher on my list (sites like PK are also amazingly helpful when you want to focus on a specific technique: struggling with drawing eyes? there’s a video tutorial for that; can’t quite nail down faces? PK’s got you covered!).

Conclusion: I need the support of my fellow students, at least at this stage of my art journey. I also need the forced structure of a course to make me put pencil to paper. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but it’s true.

Wherefore Art Though, Drawing Pad?

So, what’s happened with all of that artistic passion? Most of it’s in a cabinet, along with a ton of art supplies, shouldered aside by other demands (family, work, etc.).

But it’s not dead.

I still surf DeviantArt (though I haven’t posted anything, I regularly favorite other people’s art for my own inspiration), and I still find myself stopping to admire a piece of art (“how did they achieve that effect…oh, cool!”).

Over the past few years, I’ve increasingly swung my time from my traditional business pursuits to my creative interests, and I’m now entering a new chapter in my life. I’m still sorting out what this looks like, but the undeniable theme is creativity over corporate commitment.

I’ve written more in the past few years than I have in the previous ten.

Who knows? Perhaps I’ll resume churning out art or darken the door at Art Center or CDA as a student. Perhaps I’ll renew my Pencil Kings subscription. Perhaps I’ll create art based on my fiction, which was the original purpose in taking art classes to begin with.

The one thing I am confident about?

The lessons I learned from my journey into art will inevitably resurface again in the future.

Few creative endeavors truly stand alone. Can you produce art with zero design skills? Can you write song lyrics without a minimal concept of story? Don’t films incorporate nearly every creative aspect: audio, visual, narrative, etc.?

Most importantly, few creatives ever permanently abandon their passion. Including this typing monkey.