My last post touched briefly on a topic I call narrative sequencing, which refers to the order in which an audience experiences the individual pieces of content of a transmedia property. I want to explore that concept a bit more in this post.

*****

A few months ago, I woke up in the gutter, feeling a little confused and not a little surreal. Who knew reading Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics could be so dangerous?

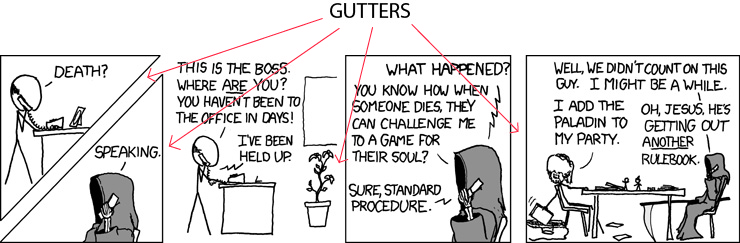

If you aren’t familiar with this book, it is a commentary of meta: a comic that discusses the history, fundamentals and theory of comics. One of the many concepts McCloud discusses is the ‘gutter’ – the space between panels or images. McCloud goes into a wonderful explanation (pretty heady stuff, actually) about the theory behind gutters and how they are used in comics.

Ultimate Game by xkcd.com, CC BY-NC 2.5

McCloud explains that the gutter (what’s not on the page) is as important as the images it separates (what’s on the page). It’s a terribly Zen kind of thing. The image not drawn has as much to do with the unfolding of the story as what’s actually shown. Instead of being blank, empty space, the gutter has a form and shape as much as actual images.

More importantly, the gutter is where the magic of comics happens, because that’s the space the audience has to fill in. I say ‘has’ to, because as soon as the reader moves from one panel to the next, they automatically begin stitching the two panels together.

Don’t believe me? I challenge you to try this experiment with any comic: try moving from one panel to the next without mentally filling in the blanks. Your brain doesn’t say, “Wait a minute, how did I go from this guy flying over a building to that woman tied up on the railroad tracks? This second panel must be the start of a new comic!”

Instead, your brain infers that there is some logical connection between them, and it immediately begins helping the artist by coming up with the narrative linkages needed to connect the panels. Your brain helps maintain the narrative continuity and coherence of the individual panels.

We are creatures of pattern recognition (hat tip to WIlliam Gibson). We can’t help ourselves.

Of course, this concept of consciously deciding not just what to show, but more importantly, what to leave out, has applications across so many artistic endeavors. How much of a character is shown in a film/TV scene? What’s the rationale for scene cuts in a film or TV show (i.e., what is the audience expected to perceive or fill in between the two scenes)? For fiction, how do authors sort through the immense amount of information they could tell and filter it down to a subset selection that renders a better, tighter, more fulfilling story?

As creatives, we are forced to frame our story before we can share it, and the act of framing necessitates an act of editing.

image by jin thai, CC BY 2.0

There are three things I took from this Eureka! moment after reading McCloud’s book.

1) Before we can create, we must frame/edit.

2) Editing is at least as important as creating, probably more.

3) We rely on and must trust audiences to fill in the blanks in our stories. We don’t have a choice, and neither do they.

These are not earth-shattering revelations to artists, especially the good ones. But these concepts take on tremendous importance and have critical implications for telling multiple stories across multiple mediums. Storytelling that crosses media. Storytelling that unfolds in a transitory way, if you will. A kind of trans-…well, you get the point.

One of my early, but indirect, exposures to the importance of the gutter in transmedia storytelling was Geoffrey Long, who likes to refer to the ‘negative capability’ in transmedia storytelling. Long defines negative capability as, “the artful application of external reference to make stories and the worlds in which they are set even more alluring” (Transmedia Storytelling: Business, Aesthetics and Production at the Jim Henson Company, June 2007). Long is talking about how individual pieces of content can reference each other, thereby pulling audiences through a series of content pieces. For example, a comic may have a single reference to a character that does not appear in the comic but does appear in the video game. The reference in the comic becomes a migratory clue to the video game, where part of the narrative can continue if the audience member chooses to follow the clue. Now, Long was talking about the gutter indirectly by discussing how to leave the equivalent of bread crumbs for audiences to help them move between pieces of content within a transmedia property.

Then there is the concept of implied spaces, which refers to the tendency of audiences to proactively fill in the blanks of commercial entertainment through user-generated content (UGC). Fan fiction and art are the most common examples of audiences contributing their own stories as way to flesh out the world beyond what the original author/creator provided. Audiences look to the implied spaces and fill them with their own ideas and stories.

The reasons why audiences like to draw outside the lines of commercial entertainment and the ways in which they do so are varied and, at times, complex. What’s important to recognize is that audiences are acting less like passive consumers and more like active collaborators.

These aspects of the gutter are fascinating and have been explored by many in great detail. In fact, they’re crucial to the collaborative commercial entertainment model my company works with, but that’s not the nuanced point I’m trying to get at.

I’m intrigued by the gutter itself and the creative side of this process. What are the narrative challenges and possibilities that the transmedia gutter poses to creatives? Whether you are fracturing a story across multiple mediums or telling multiple stories across multiple mediums in a shared world, as soon as you decide to produce more than one piece of content, you have the artistic challenge of determining the relationship between those pieces and the audience.

It isn’t the simple matter of trying to guide audiences from one piece of content to another, with audiences stringing the content together to form a story (though that’s also important). Rather, creatives must critically look at what was not shown between the pieces. If the ARG precedes the comic which precedes the novel, how will audiences fill in the blanks between them? What can creatives do to shape how the audience connects them?

As I mentioned in a couple of previous posts, creatives have lost absolute control over not just the order that audiences experience their content but also the format for that experience (on this post and also on this one).

And my last post already highlighted the challenges for transmedia storytellers attempting to guide audiences through a particular, preferred narrative sequence.

So, how do transmedia storytellers overcome those challenges? I propose that the solution to the challenge is in the creative potential of the opportunity. Creatives should be working on the transmedia gutter itself as much as they do on what’s in between the gutter.

As audiences move from one content piece to another, what information do they have? What information is missing? How does the missing information affect the story? Is it trivial (John prefers his eggs over easy), important (John has a history of violence), or purposefully misleading (John was framed for the attack on the night clerk and is actually pretty harmless)?

The gutter can be filled with hints, suggestions, or intrigue. It can swallow time. It can bridge creatives with their audiences in a personal, one-to-one way (after all, we can only fill in the blanks with our own personal thoughts, beliefs, and experiences). It can be dark, even scary. But the darkness is something to be narratively mastered, not feared.

At the risk of repetition, transmedia storytellers must incorporate the gutter between content into the story as much as they do the gutter within content.

For native transmedia, the gutter can be a beautiful place to craft stories, one which can work to integrate multiple pieces of content and support multiple narrative sequences that maintain coherence and continuity. And it’s there, in the gutter, that collaboration between story tellers and audiences happens almost without notice.

You can find magic in the funniest of places…

Scott’s book, the whole series in fact, is eye opening and mind expanding. The concept of the gutter as well as his graph of realistic vs representational vs iconic are useful when applies to so many other fields.

The most popular model for transmedia storytelling I have seen to date seems to favor a dominant or preferred medium for the experience, whether it is a native transmedia work or one that is first and foremost a book/movie/CD. In these cases, the entirety of the transmedia experience exists within the gutters of the dominant story, so understanding and appreciating this gap-filling seems particularly important to crafting a compelling narrative.

Since transmedia storytelling fills in many of these gutters, it’s equally important to carve out safe playgrounds for the creatives (whether it’s through the transmedia production team or user-generated content) to explore. Sometimes, information that falls between the cracks should remain unfilled: and there needs to be a clear method of communicating that.

NovySan – Completely agree. McCloud’s coverage of the medium and genre is as originally presented as it is comprehensive.

Michael – Fantastic point about communicating clearly how, when, and where audiences can collaborate. Truly critical to building trust of audience and encouraging collaboration.

The interesting thing about the gutter for me is the difference – albeit highly nuanced – between it and the ideas of negative capability and implied spaces. In my mind, the gutter is what makes negative capability and implied spaces possible.

Also, no matter how much gap-filling occurrs (whether by creators, collaborators, or audiences), there always something left unsaid. No matter how much content you throw at a property, you can never fully fill it. For every contribution, there is, by definition, a new gutter of unsaid, undrawn, unshared stories. And possibilities.

Oh this is important, thank you, it gives a name to something I’ve perceived but couldn’t articulate clearly.

My experience as a collaborative artist has been that there’s always an interesting conversation between those who wish to nail everything down and those who want to keep it all free. Now I see that that’s a conversation about the size and nature of the gutter.

My argument has always been that no matter how much stuff you nail down, there will always be gaps that some people will fill in for themselves (and always in unexpected ways) so why put so much energy into the nailing?

My interest is in creating as wide a gutter as possible. How far can you go? How much structure do you need your story to have? Or rather how little structure can you get away with?

Good thinking material, thanks, Scott!

Lloyd – There are, happily, limitless ways to (un)structure both the gutter and the collaborative nature of a project. Kudos for pushing the creative envelope!

Thanks for including me – and my work – in this great post, Scott!

Funnily enough, one of the great motivators for me to turn that thesis into a book is to clarify something about negative capability that only really came into focus after the thesis was finished. The “capability” in negative capability is in the *audience*, not the *artifact* – so that those deliberately-crafted references to people, places, things or events external to the current component of the franchise, those openings which serve as rabbit holes (or trailheads, or whatever you want to call them), aren’t the negative capability, they’re the *negative spaces* which the *audience’s* negative capability – the capacity of the human imagination to fill in those spaces without breaking the suspension of disbelief – essentially glosses over with a tantalizing bit of customized imaginative spackle until the storyteller can come back and fill in those gaps with additional stories (frequently in other media) later on. So the whole “who’s under Boba Fett’s helmet” mystery from our childhood is an example of negative space – the mysterious identity – trading on our own negative capability – our imaginations – until Lucas could come back and poop all over it with the prequels decades later. (Okay, maybe I should have chosen a less personally loaded example, but you get the idea!)

Geoff – love the clarification, specifically as it relates to the collaborative nature of audience response to and participation in world building and extension. Keep me posted about the book!

Hi Scott, thanks to the link back to this post.

I am reminded of a screenwriting panel I was at about 5 years ago. The writer on stage was paraphrasing someone very well known and successful (I’ve long since forgotten who it was sorry!) and extolling the virtues of using the cut to tell the story.

As you say The difference / evolution of that with transmedia is that the gutters/gaps are more than inference within a story, they can lead across platforms and potentially bridge IPs should they find a way to merge.

Last thought: If you were to make a film or comic without gutters, made of scenes repeatedly like this.. show a house, show the phone ringing, show the woman get out of her seat, walk across the room, open the door, walk down the hall and, and, and eventually answer the phone < that's a pretty patronising way to treat your audience and a fast way to bore them. Crafting gutters/gaps in single/multi/trans media is a great way to show respect to people who have given their time to your world and who doesn't respond well to that!?

I love it – the gutter is a way to show respect for the audience! : )